An unforgettable work exchange in Western France

I cherish my work exchange spent with my Worldpackers host on his farm in Brittany, France. I fell in love with mushroom hunting, cooking, the French lifestyle and resourceful living.

11min

Worldpackers sponsored my quarter-life crisis. I was working in publishing for two and a half years after graduating, a lifelong dream of mine because I've always loved books. I knew books were timeless and they'd never go out of style. But the gratitude for being there began to give way to burn out. I chased raises and titles and recognition; yet these quickly evaporated. Nothing seemed to satisfy my mounting frustration.

It took about a year of patient waiting (mixed with bouts of anguish and emotional turmoil) for the answer to become clear in a dark yoga class. A whisper rose from within and said: take the trip. At that point I had no idea what the trip was, or where I was going, all I knew was it was finally time.

It amounted to this: the suffocation of staying still became scarier than the risk of jumping.

So I gave my notice and set off in search of what my next chapter would look like. Because I didn't really know. And it's okay not to know. It's okay to tell people that you don't know. That you're stepping away to walk around and think a while. I just knew it was time for a new dream, something to bring me back to life with joyful intention. (If you could do without the walking, Worldpackers is a great option if you like freedom but hate planning or spending money).

I chose to be open, depend on my intuition, and trust that everything would unfold as it was meant to. It's a beautiful, empowering feeling stepping out alone. Deciding that you don't have to wait for anyone to open up the door for you.

I didn't know this then, but you can only find your rhythm if you go alone.

Fast forward

After my 40-day walk through Spain I had plans to meet a friend in Portugal for a week or two. After that I just knew I couldn't see Europe for the first time without saying hi to France. It was about time that I met her. Certain je ne sais quoi...

I was able to find Worldpackers hosts in France that provided free accommodation and meals. Bingo. Light gardening and housework? Psh, easy. That sounded like a vacation after 40-hour weeks and trying to explain what a desktop is to a professor who can't use their computer. (Side note, I still really don't know how to explain the concept of your computer's desktop. I challenge you to do this with a friend. It's surprisingly meta).

And that's how I decided to join Worldpackers for my first work exchange. The opportunity? An eco homestay in Melrand where I'd help in my host's garden in exchange for a quiet room of my own and garden-to-table French cuisine.

An unforgettable work exchange in Western France

90 low quality minutes of Lisbon hostel sleep later, I arrived in Paris. Man, did Paris hate me. The Charles de Gaulle metro was conveniently undergoing construction leading my haggard ass into the frantic sardine can of her underbelly. The stress, the shoving, the dim lighting; I felt like I was in the basement of a sinking Titanic. In those situations, I am grateful to be tall but not so for my awkwardly bulging backpack that was heavier than I previously remembered.

I was ushered outside by sorely underpaid airport attendants in vests; my jacket had just been hostel-snatched, and I smiled at my own underestimation of the bitter November air.

It was a bad first impression. Neither Paris nor I were putting our best foot forward.

A few bus detours, confused metro-mounting and dismounting later, I met my Dad in Paris. He had just landed a big ole United airbus so the timing was perfect for a lovely dinner, Camino stories, and free plush hotel room.

In the morning I lovingly accepted his parting gift of the razors and period supplies I'd requested from my mother, and took a bus West to Rennes to meet my Worldpackers host, David. The great thing about Rennes is its easy for outsiders to say and pronounce, which is not the case with many other French cities.

Fun fact about Rennes: you'll spot fake radishes all over the city (about 600 total), in a light-hearted attempt to make the city la plus radieuse de France (a pun on 'most radiant town' doubling as the 'most radishy'). Who says the French take themselves too seriously?

Local artist Ar Furlukin says the radish is a "symbol of our common roots" and adds: "There's an idea that we're all part of the same bunch, even if we're all different."

Radishes aside, Rennes also has beautiful bridges (France embraces her many rivers), and a boastfully modern train station touted to be the best in France.

But Rennes, for all her humble charms, will always be the heart-stopping place where I nearly took up residence in a McDonalds for the night.

And you just don't get far from a feeling like that.

So don't use BlaBla Car, kids. You will get stranded and die.

My car-share arrived six hours late, so when I finally met my beleaguered host David it was past midnight (always a great first impression). I clenched my jaw, clutching the door as he zoomed through pitch-black winding roads wondering what in the world I'd gotten myself into.

First 48 hours in France aside, my three weeks doing a work exchange in autumnal Melrand changed my mind. France didn't hate me. In fact, she loved me deeply. She was simply hurt that it took me so long.

Waking up that first morning, Melrand dawned on me like a hug. I finally had my own queen plaid bed with no bed bugs or hostel thieves afoot. I had a nightstand and my own dresser and a fireplace and a non-communal bathroom!

David, was lively and chatty, a stark contrast to the mute mannequin turned lady lamp (also wearing plaid) lounging behind us in his living room. I want to say her name was Trudy... we spoke of her often in my three weeks there. I sensed she represented the feminine energy that bachelor David was lacking in his life. Either way. Trudy was a presence. She never warmed entirely to me nor I to her.

After our breakfast of coffee and toast with David's homemade jam, we set off in his death-trap, I mean BMW, for the woods, gratefully only a five-minute drive away. The forest was the epitome of fall; the spectrum of yellow, orange, red enveloped us.

I was on shaky ground. Not only because I couldn't tear my eyes away from nature's colors or the towering ferns, but it had rained the previous evening so the forest floor was slick with damp leaves. (Mornings after rainfall are the best periods to scavenge for mushrooms, by the way.) Luckily David gave me a poking stick that steadied me often. It's a cheap hobby mushroom hunting; all you need is a dense wood nearby, a poking stick for checking under the leaves, a knife to sever them from the ground, and a bag to put them in.

We mostly collected two varieties in our weekly excursions, Cep's and Girole — I'll spare you the phylum genus bullshit. Cep's (pronounced "sep"; also referred to as a "penny bun") are revered as the King of the Edible mushroom. Easily identified through its thick, rounded stem. The local Melrand farmer's market had these baddies bagging at €10/kilo.

My very first find turned out to be my greatest of all our six ventures into the woods. About ten minutes in I looked down from where I stood and found one Cep eight inches high beside my boot. Just like that. She was round and chubby like an acorn, her cap was a humble brown, at least seven inches across. King of the edible mushroom.

My, how the magic of that discovery continues to dawn on me. From that moment on, the mystique of mushrooms was in my bloodstream.

Girole, or "chanterelle" mushrooms are golden yellow, the easiest to spot amongst the hazel forest floor. Their blooming cap mimics a flower. Highly sought after by chefs, but for whatever cosmic reason, animals have no interest in them.

(Chanter in French means "o sing", "elle" is woman).

While writing this article, I discovered that chanterelles have a public relations issue: "We think of them as promiscuous in their plant relationships, because we have found their mycelial threads intertwined with the roots of hardwood trees, conifers, shrubs, and bushes." And this slut-shaming isn't the end of it. The scientific shade has leaked over onto their black cousins, who are inaccurately dubbed "the trumpet of death." Completely false: They are both edible and certifiably delicious.

A few fast facts for aspiring foragers:

- In general, you want to avoid gills underneath the cap.

- Wherever you find one, stay a while, poke around; there's likely a few friends nearby as they scout the good spots and proliferate.

- Mushrooms are like snakes; the brighter, the badder. The image below is an Amanite mushroom, bright red and highly toxic.

- Oh, and you know that saying “Be patient with yourself; nothing in nature blooms overnight?” Mushrooms bloom overnight. But by all means still be patient with yourself.

One last thing while I have you here because mushrooms are fascinating: there's a tenuous, highly mysterious (read: scientifically unsupported) myth that mushroom "flushes" (aka mushroom blooms) coincide with the full moon. So do babies, heart attacks and murders, by the way). This connection is still mysterious and poorly documented, but who knows, perhaps it's my opportunity to obtain a Fulbright for mushroom study in France.

I digress, it also raises the undeniable question of whether we should group all edible fungi, a rather sprawling number of organisms, under one umbrella (lol).

Mushroom hunting was my favorite part of my work exchange in France, which essentially consisted of helping David on his farm alongside our evenings sharing meals and conversation. The morning hours would fly by in the quiet forest as we focused singularly, I'd find all worries wiped from my mind, and a deep sense of peace. Not to mention the ecstatic joy of discovery.

David was a fascinating man, originally from Britain, he'd relocated to Western France about 15 years prior. "In France, it's less about success and material wealth than it is in England," he'd once told me.

My perception was the same from the short time I spent there, it felt like I was back in time. Everyone raised their own garden, listened to the radio, didn't put much focus on how they looked or what they wore.

One of David's friends, Olivier, who lived in a transformed trailer off the grid (aka no plumbing) raised a fair point about how the trend away from personal gardens has placed pressure on the government to feed you, leading to factories of cheap, over-salted, fake food. It makes you wonder, should everyone be responsible for feeding themselves?

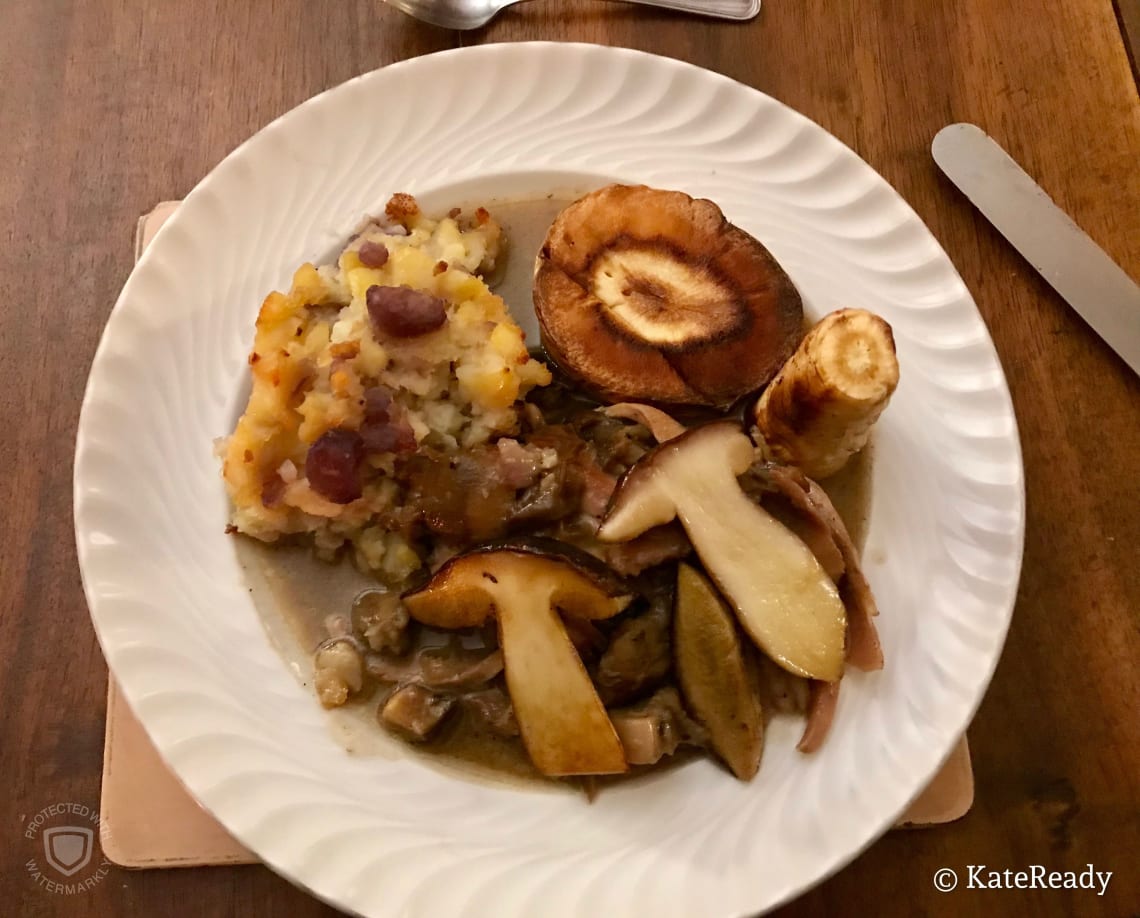

A dynamite chef, David had been encouraged by the Melrand community to open his own local restaurant, but it never came to fruition. We'd enjoy delicious meals of mushrooms in gravy, pheasant curry on couscous powder, or his risotto, culminating in homemade lime cheesecake topped with flower petals or pear crumble. All straight from the garden. I have never cleaned so many plates in my life.

I asked David to describe Brittany, the region of France I found myself in, and he said: "we prize our sense of independence; we also have a reputation for the most drinking and drugs."

David, in his fifties, was highly intelligent, animated and political; we'd listen to BBC radio or watch Agatha Christie murder shows in French. He'd teach me how to soak jars, then scrape the labels off to preserve ratatouille or confiture. I learned from watching David how to prepare thinly-sliced potatoes au gratin. I trimmed lavender, varnished furniture, painted chairs, and rescued flower cuttings to be replanted in the spring. On good days I passed the afternoons peeling pears and carrots in the garden; on others, I scrubbed cursedly at the shower, googling countless homemade grout cleaner recipes (time-saving hint: none of them work).

I learned that the following should not be composted: eggshells, onion peels or lemons. Eggshells take years to decompose, onion peels and lemons are detested by animals and repulse them from foraging further.

Water for soaking carrots should not go down the sink.

We'd chat openly about 9/11, what really happened, and how Princess Diana's assassin lived in the next town over, in Lorient, and that he wasn't known to be a drinker.

He'd vent about Brexit; how he suspected the politicians were sending a bad bill through in the hopes it would dissuade the populace from moving forward with it at all. In a strange, dark comfort, Britain sounded a lot like America; divided, acrimonious, stewing in rancor. The rise of the Alt-Right was also burgeoning in Germany, due to fears stemmed by the refugee crisis.

One afternoon on our way home, after a few hours flew by mushroom hunting, Patti Smith shrieked over our car radio: "We don't need presidents, we need PROPHETS!"

On November 11th, my fifth day in Melrand, we walked into the town square (a few hundred feet from his door) for the centennial anniversary of WWI. 100 years had passed since the armistice. All of Melrand's inhabitants had gathered, around 150 people, solemnly listening to the mayor. My French isn't quite advanced enough for me to sum up what was said, but in essence elderly men from the town who had served accepted medals, plaques and copious applause for their service. The school children all held homemade French flags made of paper and sticks. I chuckled a bit at the mismatched flags, how the order of the three colors varied here and there. No condescension, it added to the heartfelt, homemade ceremony.

The children sang a song and left flowers on the church steps.

Next to me, a two-year-old boy was captivated with the way his flag flapped in the wind. I sensed it was his first time ever holding a flag. It touched me deeply, the simplicity of his awe.

Standing there and honoring the 100 years since WWI, I felt disappointed; far from triumphant. Feeling ultimately that we had failed to learn from our violent past. From the violent catastrophe of WWI. Feeling like we were still following those bloody footsteps into nationalism, xenophobia, and arms-building.

Eleanor Roosevelt returned to my mind; I'd read Joseph Lash's biography of her recently and remembered how she had toured France after WWI, meeting hospitalized soldiers and civilians, saw battlefields divided by trenches and abandoned bloody barbed wire.

Like her, I could not help but feeling "as though the ghosts were beside me." As though we were letting them down.

As David so often said, and I experienced firsthand, the French will protest over anything. It's wonderful. It's enlivening, inspiring and emboldening. Driving anywhere that November became an anxious ordeal as the roads were blockaded across the country. The French had taken to the streets in high-visibility vests in order to protest the lowering of their speed limits coupled with the doubling of ticketing fines. In house windows, in cars, in buses, in stores, French citizens would display high-vis vests to express their solidarity.

French citizens of all ages would go out, day after day in the cold, stopping cars, making their voices heard. The speed limits were lowered, ticket fines doubled, but were any improvements being made on public transportation? No. Were gas prices steadily rising? Yes.

Sometimes a raw deal calls for an orange vest.

I woke up one morning during my work exchange in France and realized that it had been a long time since I'd asked myself if I was happy. I smiled. What a beautiful omission. I hadn't needed to, I just was. When you are happy, you don't find yourself wondering about it.

Merci, David!

Janaína

Jun 04, 2019

I really enjoyed reading this, Kate. Thanks for sharing such a unique experience!

Patricia A.

Jul 18, 2019

Kate, I enjoyed this so much—well done! PLEASE keep writing. I see a future for you in journalism or other authoring!

Yacine

Apr 22, 2023

Oui👌